March is Women’s History Month, offering a great opportunity to review issues related to women in the criminal justice system. Criminal behavior does not discriminate by gender but women in particular have a greater lack of services upon entering this system. At the SAW Project, we promote changing supervision practices so that offenders can reside in their home, parent children, maintain jobs, and pay taxes; all while being held accountable for mistakes made to society. However, when it comes to female offenders, our program models appear to be making fewer advances.

In recent years, the number of women and girls in the criminal justice system has exploded; many subjected to increasingly punitive sentencing policies for nonviolent offenses. Evidence shows that female offenders have biographies and histories that are very different from those of men. They may struggle with greater substance abuse, mental illness, and histories of physical and sexual abuse, but few get the services they need.[1]

The World Female Imprisonment List (third edition) shows the number of women and girls held in penal institutions from 219 prison systems of independent countries and dependent territories. Findings show that over 700,000 women and girls are being held in correctional institutions throughout the world. A little over 29% of these are held in the United States (205,400), with China (103,766), the Russian Federation (53,304), and Thailand (44,751) following.

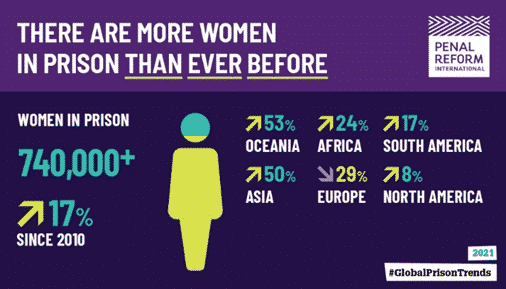

Information provided by Penal Reform International shows increases on most every continent.

While institutions designed for men should be modified to better meet incarcerated women’s needs, an equally important goal is to improve supervision practices within the community. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) notes that reentry into American society remains one of the systems’ most significant challenges, as we release approximately 78,000 women back into communities each year, equating to more than 200 every day. Author Dr. Holly Miller recommends policy and practice developments as follows:

Recommendation 1: Gender-Responsive Reentry

- Utilize actuarial screening instruments for substance use disorders, psychiatric disorders, and criminogenic risk that have been designed specifically for women

- Implement program elements that are gender informed

Recommendation 2: Integrated Treatment for Co-Occurring Disorders

- Screen for substance use disorders, mental illness, and chronic health conditions that may impact recovery and reintegration

- Design individualized treatment plans that concurrently address these comorbidities

Recommendation 3: Therapeutic Communities

- Return to the therapeutic community model with the intent to improve current reentry efforts

Recommendation 4: Focus on Aftercare

- Design programs so that treatment begins at least 90 days prior to release

- Make linkages to community health providers for treating addiction and mental and physical health needs prior to release

- Maintain case management while the individual is under community supervision after release

Recommendation 5: Medication-Assisted Treatment

- Use the established public health framework of medication-assisted treatment to reduce recidivism and relapse for those suffering from addiction, mental illness, and/or addicted to opioids or alcohol

Recommendation 6: Peer Recovery Support

- Utilize peer recovery specialists to capitalize on women’s qualities (stronger social bonds, interpersonal connections, etc.)

- Develop personal relationships that serve as a social support during recovery

Recommendation 7: Employment and Skills Training

- Expand reentry programs so that programmatic elements reflect the full range of risks and needs of incarcerated persons about to reenter society

Recommendation 8: Housing Assistance

- Increase funding and corresponding research to expand housing services for formerly incarcerated women, particularly those who have custody of their minor children

Recommendation 9: Maintaining Family Bonds

- Increase the amount of contact women have with their children and families during incarceration

- Allow women to interact with their children on a regular basis while in prison

- Offer parenting classes when appropriate

We can learn about many practices that will improve outcomes for women leaving institutions to reenter society. But studying these better practices won’t help if we don’t implement the necessary changes. Therefore, during this Women’s History Month, I’ll ask the challenging question:

“What could you change in your community to help supervised women be successful?”

[1] https://www.aclu.org/issues/prisoners-rights/women-prison/pregnant-women-prison